Paige Compositor

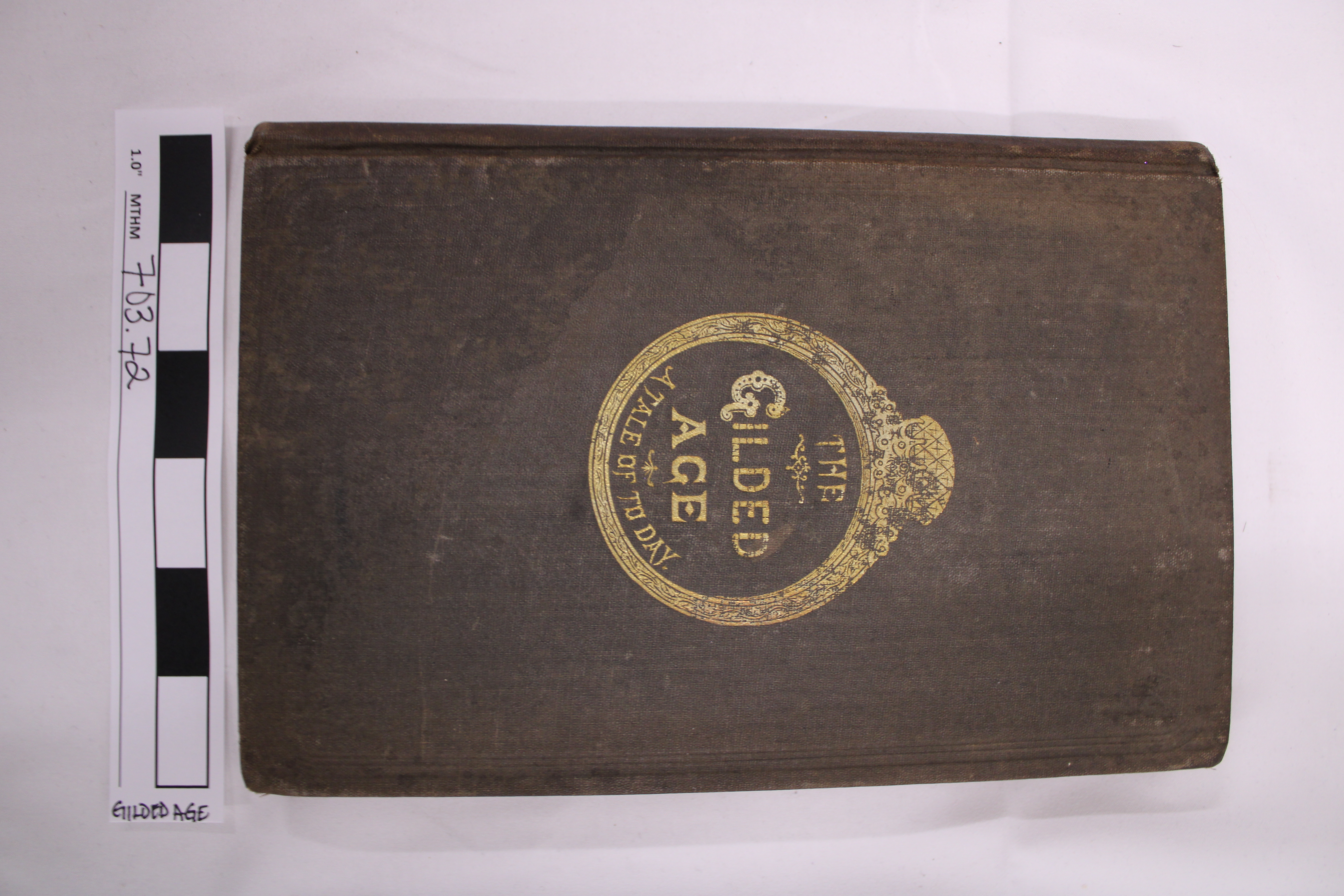

Today we have computers and modern printers, but back in the Clemenses’ time, Samuel would have to write his stories out by hand, or use a typewriter, and then rely on a publishing company with printing presses to make copies of his books for sale. He couldn’t just print off a bunch of copies the way we would today.

With early printing presses, each page of text would have to be manually laid out using small wooden or metal blocks each with either a letter, symbol, or space on them. These blocks were arranged to form the text to be printed on the page, inked, and then passed through the printing press with a piece of paper to create the typed page. For each page the process had to be repeated and eventually you’d have a complete book or newspaper.

At age 11, Samuel Clemens left school and started his first job as a printer’s apprentice. He set type for a local newspaper and lay out all the letters for each page. He would sit at a table next to a cabinet called a type cas in which the drawers contained compartments to sort and store each letter and symbol that could be used on a page. What we now refer to as upper-case and lower-case letters got their name by where they were located in the case. Upper-case letters were located near the top and lower-case letters near the bottom. Clemens loved the printing process and called printing “the noblest of all arts, and destined in the ages to come to promote the others and preserve them.”

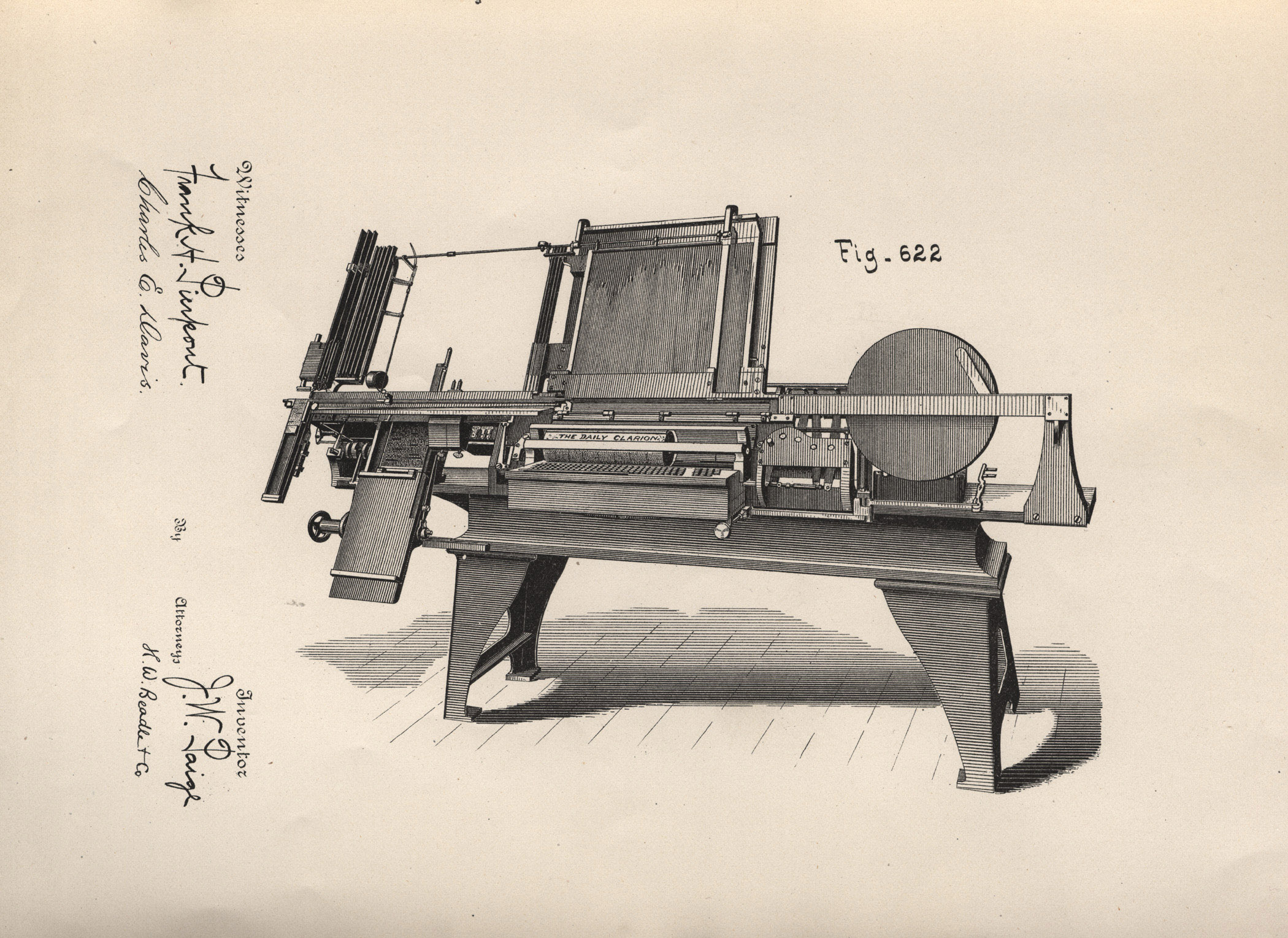

James Paige was trying to invent a machine that could automate the typesetting process – so instead of a person having to place each letter block by hand, the Paige Compositor was supposed to set the type for you – more like a typewriter would–if you typed the text in here. It was supposed to produce many copies in a short period of time, making the printing process cheaper and faster. Unfortunately, this machine never worked. It was too complicated, the parts kept jamming, and other inventors came up with better ways to accomplish the same goals. For instance, the Thorne typesetting machine was invented here in Hartford around the same time Paige was working on his machine, and it worked a lot better,

Samuel loved technology and around 1880 he started investing in James Paige to help him develop his invention. As an investor, Samuel didn’t just supply money, he also had a lot of experience working in printing that he was happy to share with Paige. There are many letters between Samuel and Paige discussing all aspects of the compositor– the design, its potential uses, the costs, and the speed.

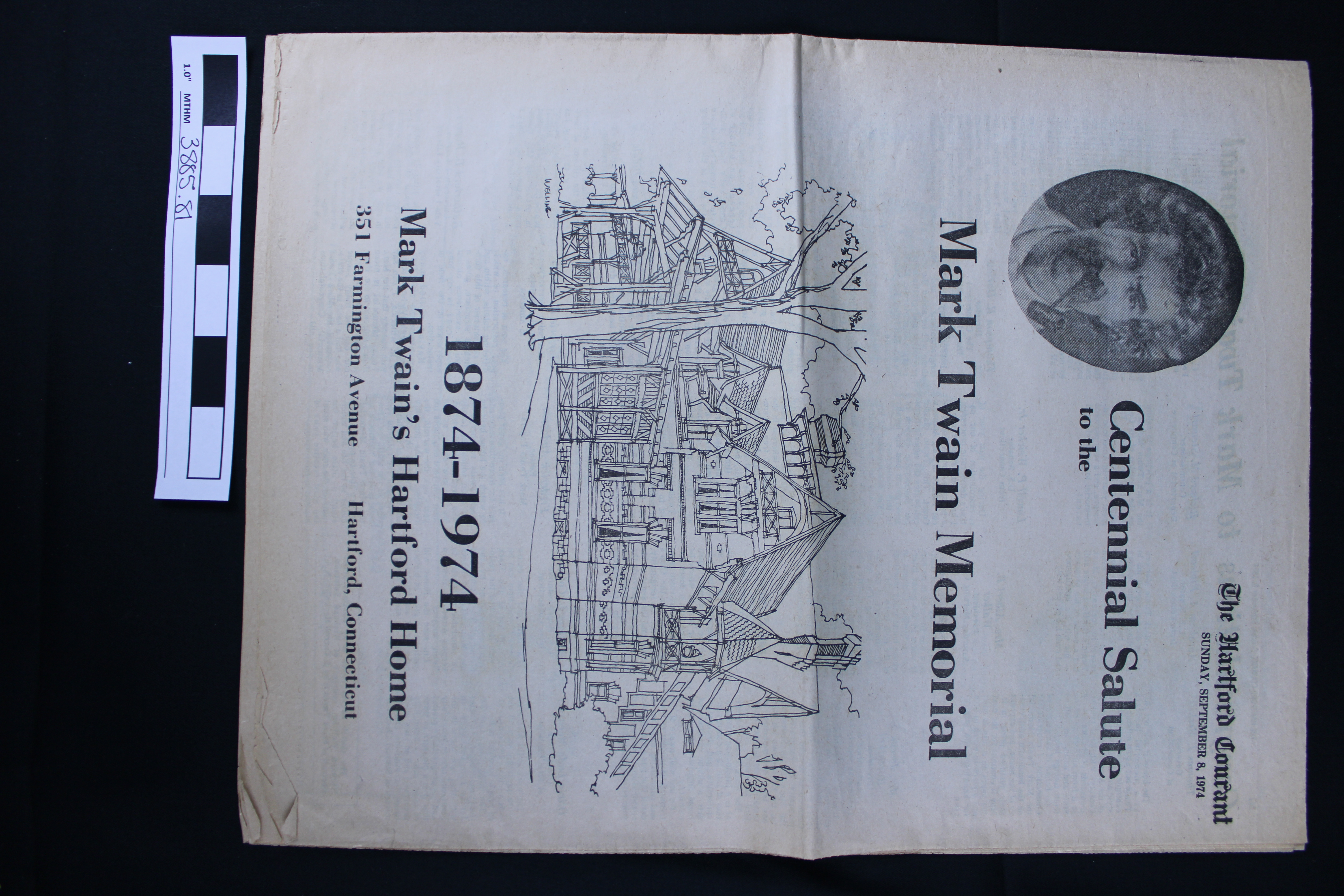

In one 1886 letter, Samuel asks Paige how his machine’s capabilities compared to what skilled workers could do with the methods that already existed. After all, if the machine couldn’t do this work faster, cheaper, and/or more accurately than people, why would any printer want to buy it? Samuel proposed a competition that would test the skills of human typesetters, so Paige would know what he was up against. He suggested using the typesetters who worked at the main newspaper here in the city, the Hartford Courant. Clemens wrote:

Go to Mr. Hubbard of & ask him to assemble all his force some afternoon for a trial of speed—ostensibly at somebody else’s desire, not yours. You don’t want to be known in it. Give all the men the same paragraph—of reprint—a paragraph containing just 500 ems SOLID, & have only one break-line, & that the last one.

$15 or $20 will find out, once & for good, all we want to know. Inquire how many men there are, & leave with Hubbard 25 cents for each; & $11 besides, for prizes. Charge to me.

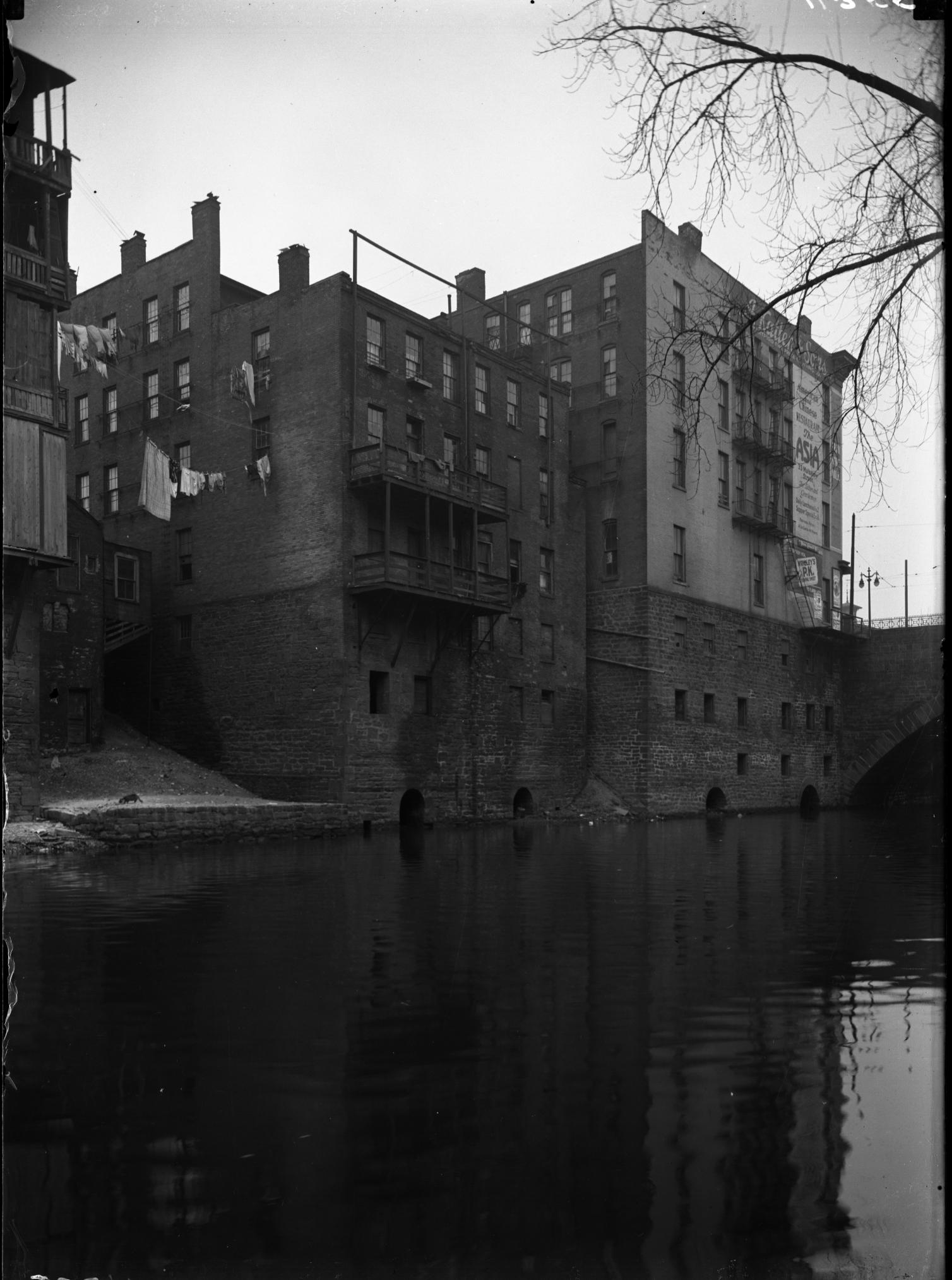

One of the reasons people were trying to invent or invest in machines like the Paige Compositor was that they hoped those machines would help them make more money by reducing how much it cost them to produce books and newspapers in the first place. Many things went into how much it cost to print books and newspapers–paper, ink, type, renting space for the print shop itself–but one of the biggest costs was the money you paid people to do the challenging and high-pressure work of setting all of this type. If Paige could get his compositor working the way he wanted to, he’d be able to sell it to newspapers like the Hartford Courant. The Courant would then be able to use the machine instead of paying all of those people. If the typesetters knew this little competition was actually helping a man who was trying to invent a machine that would put them out of their jobs, they probably wouldn’t have wanted to participate.

Only two Paige Compositor machines were ever fully built and neither went beyond the testing phase. A New York Evening Telegram article called it “Marvelously ingenious and perfect, from a mechanical standpoint; worthless commercially, the costliest machine ever built.” What really sank the Paige Compositor was that other inventions managed to do what it did not — make printing cheaper and faster than using skilled typesetters AND basically “get on the shelf” for people to buy. In particular, as Paige was still testing and tweaking his machine, its competitor, the Mergenthaler Linotype machine, invented in 1886, was already being used at the big-name publishers and newspapers.

Because of his investment in the Paige Compositor, its failure meant Samuel lost thousands of dollars (what today would be millions), had to file bankruptcy, sell his Hartford home, and move to Europe. The second machine, built in 1894, was sold as scrap metal during World War II. The original 1887 model is here, in the galleries of the Mark Twain House & Museum for you to see on your next visit.