The Rooms

Today 17 of the original 25 rooms are restored and open to the public. The others are used for staff offices, storage, or were removed or altered at some point to allow for staircases to be installed between floors. You can take a guided tour of the house and/or visit of virtual tour.

Front Hall

The entrance hall provided an appropriately impressive area for receiving visitors. Leon Marcotte of New York and Paris carved the entrance hall’s ornamental detail when the house was built in 1874. In 1881, the interior design firm of Louis C. Tiffany & Co., Associated Artists, was hired to redecorate, stenciling the room’s original wainscoting in silver, and painting the walls and ceiling red with patterns of black and silver. They drew inspiration from other cultures from the Middle East and Asia to form a design scheme that flowed throughout the first floor and public spaces of the house.

Front Hall Marble Floor

Modern restoration work on the entry hall marble floor took place in 2003. As an architecturally significant component of the house, staff worked carefully to ensure the stability of the floor; repairing and cleaning what was there, unless not repairable, and then matching old material in composition, design and color. A treatment plan based on these principles ensured contractors would properly restore the floor to accommodate growing visitor traffic for years to come.

Hallway Stenciling

The distinctive stencils throughout the hallways on the second and third floors of The Mark Twain House are another feature of the Louis Comfort Tiffany interior decoration of 1881. The normal wear on the stenciling, which was refinished during the original restoration of the house in the 1960s, necessitated a re-stenciling in 2003-04, as well as the touch-up of the decorative painting and the refinishing of woodwork. Master stencil artist Leo Sans, a German-born painter who was trained in traditional painting and stenciling methods more than half a century ago, worked on the original restoration in the 1960s. In 2003, he returned to The Mark Twain House with his son, Matt, to restore the luster to the hallway stencils and woodwork. The colors of the painted and stenciled canvas applied to the walls had become particularly faded in the 3rd floor hallway. The hallway stencil patterns were originally (both in the Clemens period and after the 1970s restoration) gold bronze.

A Mysterious Window

During the long process of restoration staff have sometimes discovered new information about the house, which then needs to be carefully evaluated to determine if something is a Clemens-era feature or one added by later occupants of The Mark Twain House. The oval interior window you can see today on the second floor is a great example of this process. When the house was restored in the 1960s there was no window here. However, evidence told researchers that at one point in the history of the house an interior window was prominently featured in the main stairwell, between the second-floor hall and Susy Clemens' room. Based on that research the window has been restored to its present configuration.

Drawing Room

The drawing room was the scene of formal entertaining. Associated Artists stenciled the walls and ceiling of this room in silver East Indian motifs over salmon pink. The large pier glass mirror that is currently on display was a wedding gift that the Clemens’ brought to Hartford from their first home in Buffalo, New York. The tufted furniture and chandelier also belonged to the family during their residence here.

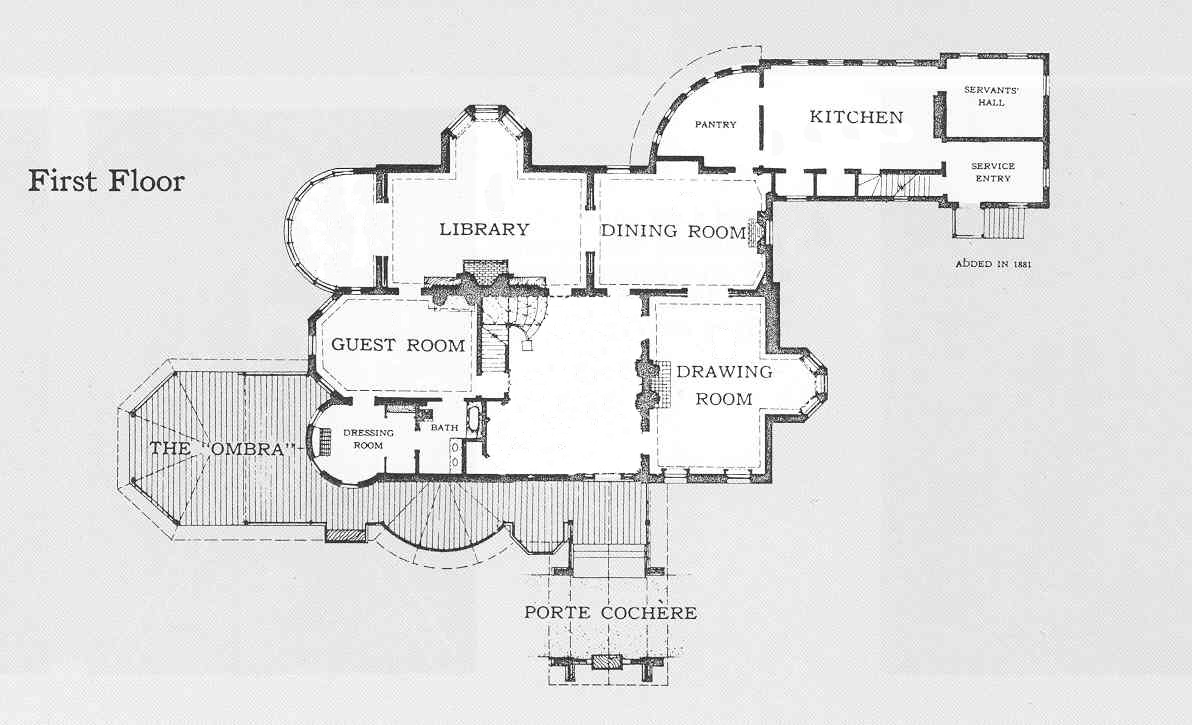

Dining Room

The family ate most of their meals in the dining room, from small family suppers to formal, elegant dinner parties. In 1881 the walls were covered with a rich embossed paper of red and gold to simulate the look of tooled leather. The pattern of lilies is typical of the work of Candace Wheeler, a textile artist and partner in the firm Associated Artists who undertook the redecoration of the house in that year. Fragments of the original wallpaper were found during the restoration, and in 1972 recreated and installed, allowing staff to showcase the 1881 appearance of the room. The walnut paneling and doors were covered with a delicate stenciling based on Chinese motifs. The kitchen and servants’ wing are located off the north end of this room.

Butler’s Pantry

The Butler’s Pantry was the domain of butler George Griffin, who worked for the family during their entire time in Hartford. This room was where fine China, crystal and the daily dishware and flatware were stored. This is also where Griffin did the necessary prep work for all of the Clemenses meals as food was passed through from the kitchen staff.

Library

The library mantel is the focal point of the library where Clemens recited poetry, told stories and read excerpts from his new works to his family and friends. Samuel and Olivia purchased the large oak mantelpiece from Ayton Castle in Scotland specifically for their library. The Mitchell-Innes family crest of the original owners appears on the overmantel, as well as the year “1874”, an alteration made by Samuel to reflect the year his family moved into their Hartford home. Samuel also added a brass smoke shield with the inscription “The ornament of a house is the friends who frequent it,” a quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson.

</span>Conservatory

Like many upper-class late Victorian homes, the Clemens home had a conservatory (a sunroom or greenhouse). Theirs had a fountain and was filled with lush, thriving plants. Clemens' daughters Susy‚ Clara, and Jean called this room “The Jungle.”

Gardeners from the UConn Extension Master Gardeners program arrived at the Mark Twain House in 2009, and immediately went to work researching the Conservatory, learning not only about the plants that grew there but some of the room’s construction – the white marble-chip floor, for example, and the constantly playing fountain. The conservatory was an important element of the Victorian picturesque architecture that inspired the house’s architect, Edward Tuckerman Potter.

The star of the Conservatory is the creeping fig, often referred to as “Ficus” from its Latin name, Ficus pumila. This fig came to the house through a Clemens family connection. One of those active in the 1960-74 restoration of the Mark Twain House was architect Robert Schutz, Jr., the grandson of the Clemenses’ family homeopathic physician, Cincinattus Taft (whose bearded visage sits on top of the piano in the drawing room) and his wife, Ellen C. Taft (whom Samuel Clemens once bombarded with profanity over the phone, then blamed butler George Griffin). One day during the restoration Schutz brought a horticultural treasure to the house: a cutting from a creeping fig from his own home to be planted in the Conservatory. An ancestor of the cutting had been given to his grandparents by the Clemenses from their conservatory; this gift was a homecoming of sorts after nearly a century.

Mahogany Suite

The Mahogany Room, the best guest suite, was restored and reopened to the public in 2017. The suite meant for prominent guests is made up of a large bedroom, a dressing room, and private bathroom. Writer William Dean Howells called it a “royal chamber.” Author Grace King compared it to the castle in “Beauty and the Beast.” The space also served as a green room for family theatricals and a gift-wrapping station for Olivia’s charitable work. The restoration, made possible by a 2014 state bonding grant, involved a fascinating bout of detective work and a hunt for authentic fixtures and decor, such as a final decision on whether the bathtub had a shower, and determining what year Candace Wheeler produced her honeycomb wallpaper.

Mahogany Suite Restoration

Staff of the Mark Twain House & Museum worked with David Scott Parker Architects, an architectural firm specializing in historic preservation with extensive background knowledge of Louis Comfort Tiffany & Associated Artists, in the restoration work. Associated Artists were known to have redecorated the bedroom, but little is known about the actual decor of the rooms. The contract between the Clemenses and Associated Artists simply states that the bedroom will have its “walls and ceiling papered,” but staff have not been able to determine if the dressing room and bathroom were decorated by them as well. David Scott Parker Architects used their knowledge of Associated Artists and the practices of the time period to determine the best approximation of how the room(s) may have been decorated.

</span>Kitchen Wing

Though a later addition, like the rest of the house, the kitchen, scullery, and pantries were built to the highest standards of the time. The sinks had running water and hot water. The stove was of the highest quality. And the kitchen featured an icebox – a modern and novel invention at the time that exemplified the Clemens’ high social and economic status.

Servant's Hall

The servant’s hall is where any one who lived and/or worked at the Clemenses’ Hartford home would take their meals and breaks their workload and schedule afforded them. There is also a door where all deliveries to the house would come through so as to not disrupt the social and business calls happening at the front door. The Servant’s Hall was located in the Servant’s Wing, built in 1881 during the Clemenses remodel of their home

Kitchen Wing restoration

From 2003 to 2004, in anticipation of restoring the first floor of the Servants' Wing (previously used for museum offices), building archaeologists worked throughout the house searching for clues as to the extent and nature of the construction work done in 1881 by masons, bricklayers, plumbers, painters and carpenters. The team of specialists discovered what the Twain-era floors looked like, the color the walls were painted, how the woodwork was finished, and how the rooms were partitioned. They discovered features long hidden and forgotten, such as a dumbwaiter, and the location of sinks, gas light fixtures and speaking tubes. The cooking range space was carefully identified and a period range installed. Restoration work was completed in the butler's pantry, back pantry, kitchen, dumbwaiter, scullery, and servant's hall and this area is open to the public as part of our regular House tours.

Clemens Bedroom

The Clemens Bedroom, the private quarters of Samuel and his wife Olivia, is located on the second floor of the house. The couple’s elaborately carved bed, which they purchased in 1878 in Venice, dominates the space. Samuel kept it with him all his life, calling it “the most comfortable bedstead that ever was, with space enough in it for a family, and carved angels enough… To bring peace to the sleepers, and pleasant dreams.” Samuel Clemens died in this bed in his Redding, Connecticut home in 1910. Twain’s only surviving daughter, Clara, donated the bed to the museum in 1940.

Susy's Bedroom

As the family grew and the three daughters got older, personal space was a commodity. While all three girls used the nursery room as babies and infants, as a pre-teen and teenager the eldest daughter Susy got her own room, while middle daughter Clara and the youngest Jean shared what was the nursery.

Nursery

Clemens’ daughters, Clara and Jean, shared the nursery. (Susy, as the oldest child, had her own room.) The brass beds in the room today recall the ones that Clara remembered when she visited the museum in 1957 during the early phase of restoration. The wallpaper reproduces the original pattern by illustrator Walter Crane and tells the nursery rhyme “Ye Frog He Would A-Wooing Go” (or “Froggie went a-courtin’” as it is better known today) in words and pictures.

Schoolroom

The schoolroom, originally designed as Samuel Clemens’ study, later became a play area and classroom for his daughters. They were educated by their mother and a governess, who taught them German, history, geography, and arithmetic, among other subjects. The Fischer upright piano currently in the room is the same year and model as the one they were given for Christmas in 1880. The wall and ceiling decorations were done in 1879 by an Elmira‚ New York decorator named Frederick Schweppe.

Guest Room (Langdon Bedroom)

Many can relate to the challenge of where to put family when they come to visit. So while constructing this house and as the family grew, Olivia Clemens made sure that there was a bedroom and bathroom available for the family when they came to visit. Today we call this room the “Langdon Bedroom” as Olivia’s mother was the most frequent guest, often staying for months at a time. The furniture in the room is not original to this Hartford house, but actually came from the Langdon family home in Elmira, New York.

George Griffin's Room

While he had an apartment across town with his wife and child, family butler, George Griffin also had a room in the Clemenses’ home. His room was located on the third floor close to Clemens’ billiards room and the guest room reserved for Samuel’s special guests. Most of the other live-in servants quarters were above the kitchen wing, so the proximity of Griffin’s room signifies his importance to the family and especially to Samuel.

Billiards Room

The billiard room served as Samuel Clemens’ office, study and private domain. Located on the third floor, away from the bustle of a busy household, this room was the place where the author would write his great works, spreading out the manuscripts on the billiard table to be edited. Clemens could also relax and informally entertain friends, sometimes into the early morning hours. The billiard table currently in the house was given to Clemensby a friend in 1904 while he was living in New York City.

Clemens’ biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, wrote: “Every Friday evening, or oftener, a small party of billiard lovers gathered, and played until the late hour, told stories, smoked till the room was blue, comforting themselves with hot Scotch and general good-fellowship. Mark Twain always had a genuine passion for billiards. He never tired of the game. He could play all night. He could stay until the last man gave out from sheer weariness, then he would go on knocking the balls about alone."

Billiards Room Restoration

Guided by a rigorously researched historic furnishings plan and painstaking analysis of physical evidence (such as historic mortar, wallpaper fragments, old carpet tacks and long-forgotten paint), The Mark Twain House & Museum restored the Billiard Room from floor to ceiling in 2003-2004. In addition to the grand billiard table once owned by Clemens, resting on a reproduction 1874 "Kinver Turkey" pattern carpet and illuminated by a restored gasolier, the details help tell the story of the room. Open books, papers scattered on the billiard table and floor, and notes tacked up on the wall reflect what we know of Clemens; he was active as well as messy when he wrote.

The fireplace proved to be an exceptionally challenging architectural feature to restore. As early as the 1960s, when researchers first removed the existing brick face of the fireplace, they found a chimney mass of distressed brick, probably blackened by years of smoke migrating through the masonry joints. After much consideration, curators for this initial restoration decided that the best treatment for this feature was a fireplace face of ceramic tile mirroring the hearth (thought to be original), and wood mantel surround.

Curators at The Mark Twain House have always believed that the hearth, composed of green and red ceramic tiles, was original to the room when Clemens kindled his fires there. The floral motif of the glazed green border tiles was a common Victorian motif and the earliest photographs of the room-from the 1950s show the tiles in place. The restoration confirmed staff assumptions. Restoration work begun in 2003 revealed new physical evidence which, coupled with the only known Twain-era depiction of the room, allowed the Museum to more accurately portray the corner of the Billiard Room where Clemens sat down to write, confirming the installation of a bookshelf during Clemens’ occupancy, which was recreated.

Artist Friend's Room

The first floor was for the public, the second floor was for the family, and the third floor was Samuel Clemens domain, so the house’s final guest room was located on the third floor and was referred to as “The Artist’s Friend’s Room” which may have derived its name from Samuel Clemens’s mischievous delight in portraying himself as an artist. This was a place for a male guest to retire after a late night of drinking and billiards.