Fox & Dow

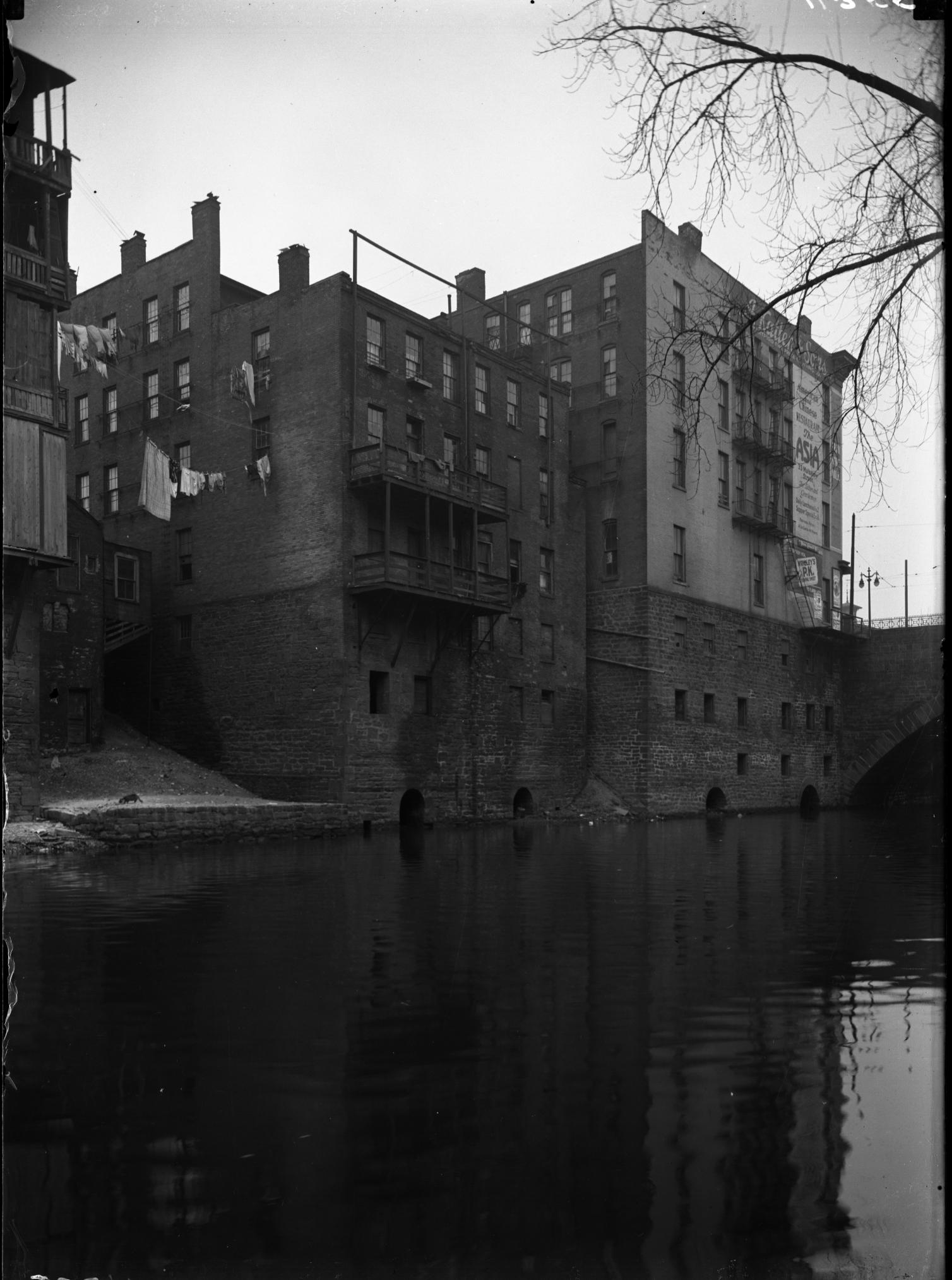

Most of the groceries for the Clemens household would come from stores on Asylum Street, Market Street and Central Row near the Old State House. Fox & Dow was one such grocer near State House Square that was frequented by the Clemens staff. All of the places they bought groceries from were close to the major transportation routes in the city, the railroad and the river, so that the produce was as fresh as it could be.

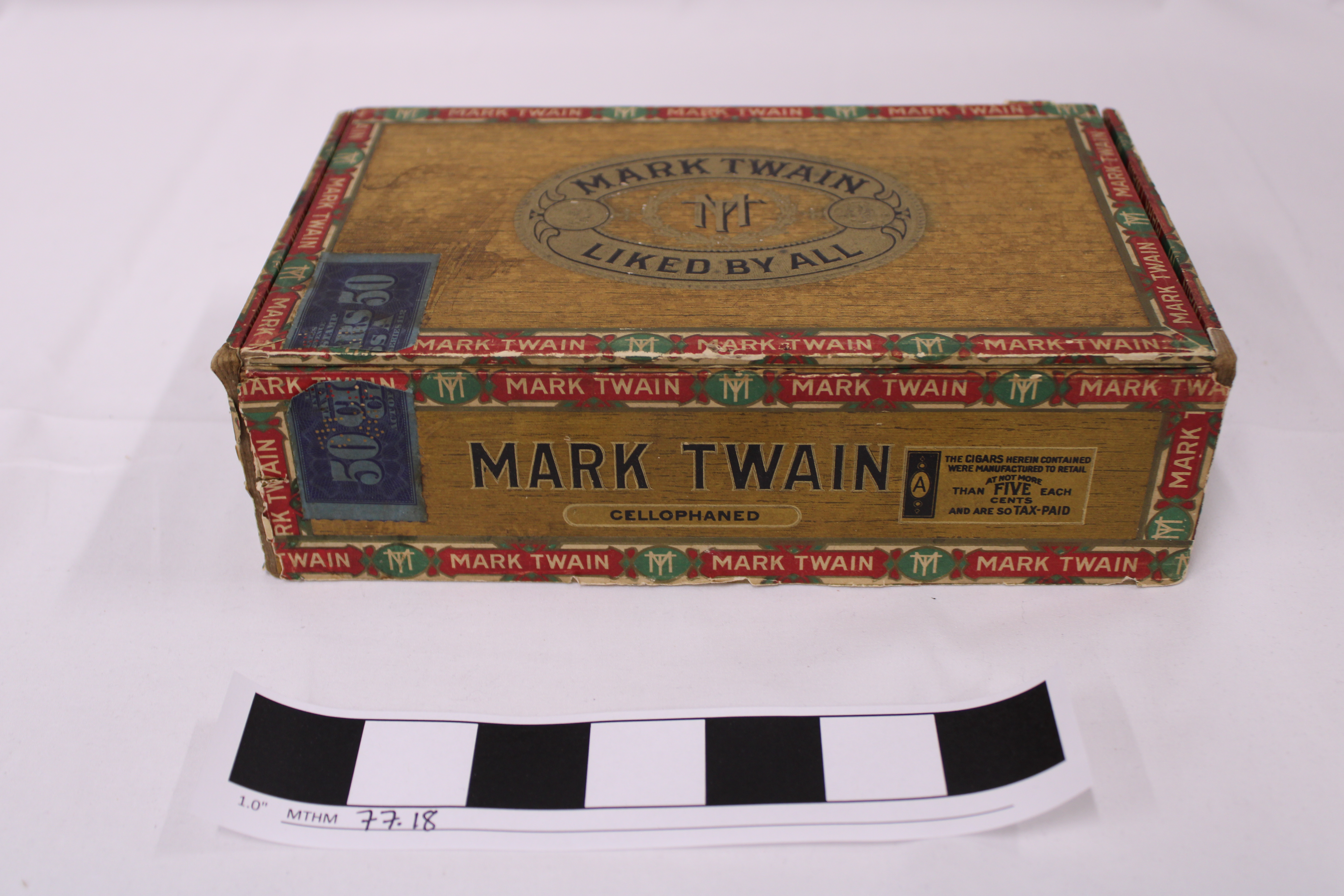

Olivia Clemens, George Griffin, and the family’s cook would work together to plan and budget for the family’s meals–both the fancy dinner parties where Samuel Clemens performed as Mark Twain, and the regular three meals a day that a family with growing girls needed. Today we might go to one grocery store and expect to find most of what we need there, but the Clemens family’s cook would need to purchase from several different stores to make one meal, no matter how fancy or homespun. She might visit five or more different people–a greengrocer, a butcher, a fishmonger, a baker, and a dry goods merchant–to get the ingredients to cook one meal.

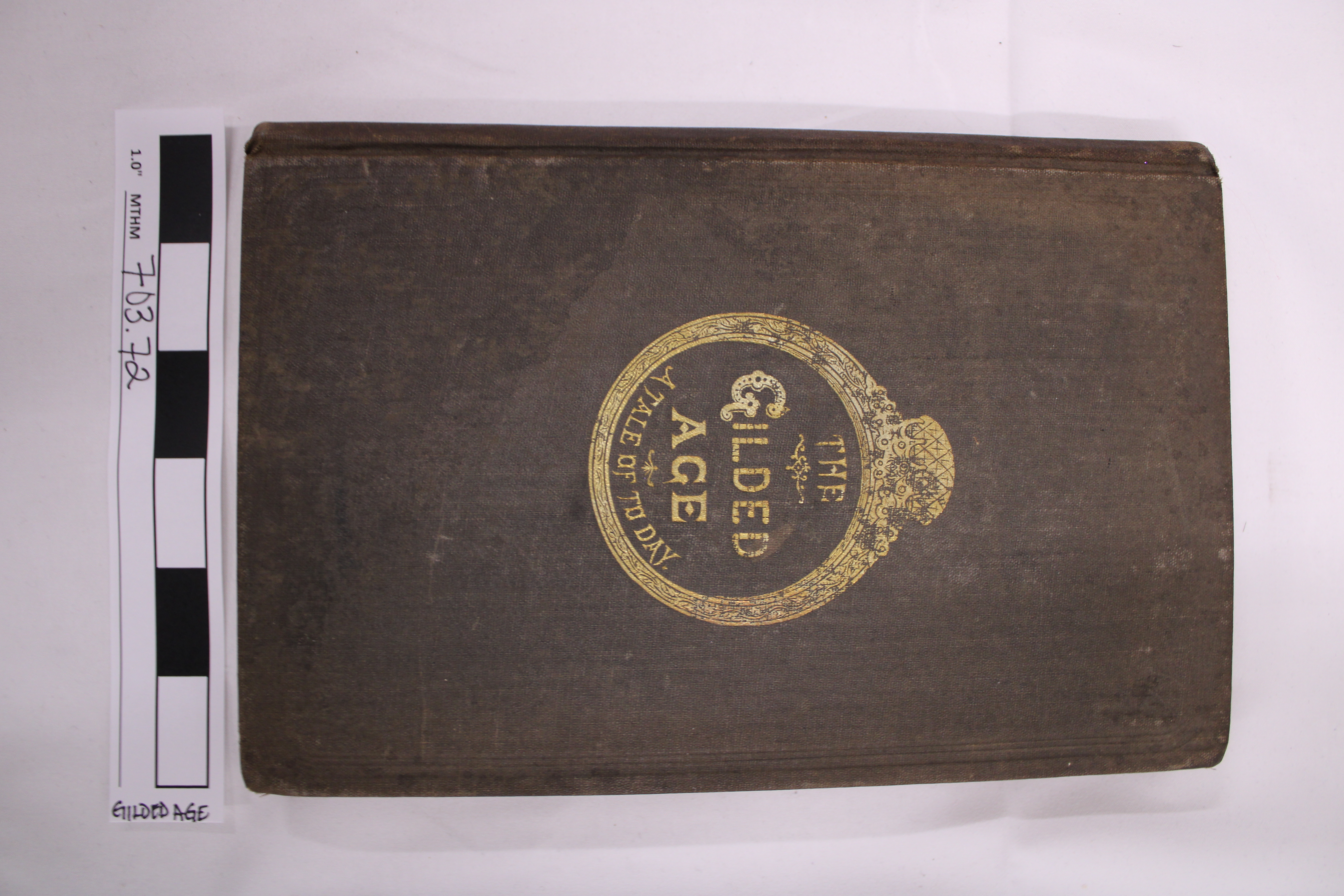

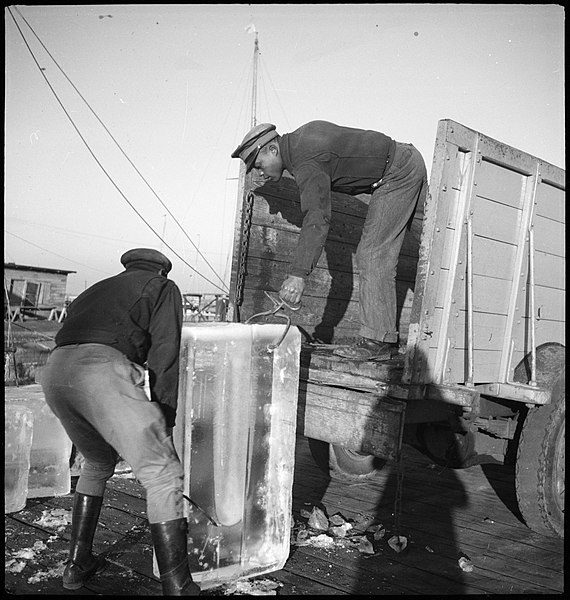

The food the Clemenses ate came from all over the world, including just down the road. A meal might be made with flour from the Midwest, turkey from Rhode Island, oysters from Long Island Sound, oranges from Puerto Rico, and potatoes from Paul Thompson’s farm in Hartford’s Parkville neighborhood. The Gilded Age also saw some significant changes in food technology and transportation that changed how people in the United States cooked and ate. Canned foods were just becoming part of people’s diets when the Clemenses lived in Hartford, making fruits and vegetables more accessible. Even chefs at fancy restaurants like Delmonico’s in New York City were excited at the possibility of being able to cook with peaches in the winter. Refrigerated rail cars were another brand new technology that had begun to shape how far you could safely transport things like meat and fish.

But how much did all this food cost compared to today? Lots of things were different about the economy in the Gilded Age that make it hard to make direct comparisons, but there are ways to put it into perspective. In 1874, the ingredients alone for one relatively simple five-course meal for Samuel and Olivia and four guests could cost anywhere between $10 and $30, perhaps even higher. The family’s cook was paid $240 a year, about $4.60 a week. Since she worked in the house all day, she would have also cooked separate and much simpler meals for herself and the rest of the staff. Others with similar (or lower) wages who didn’t have a job that provided access to meals often ate even more simply, with very little fresh meat or produce.