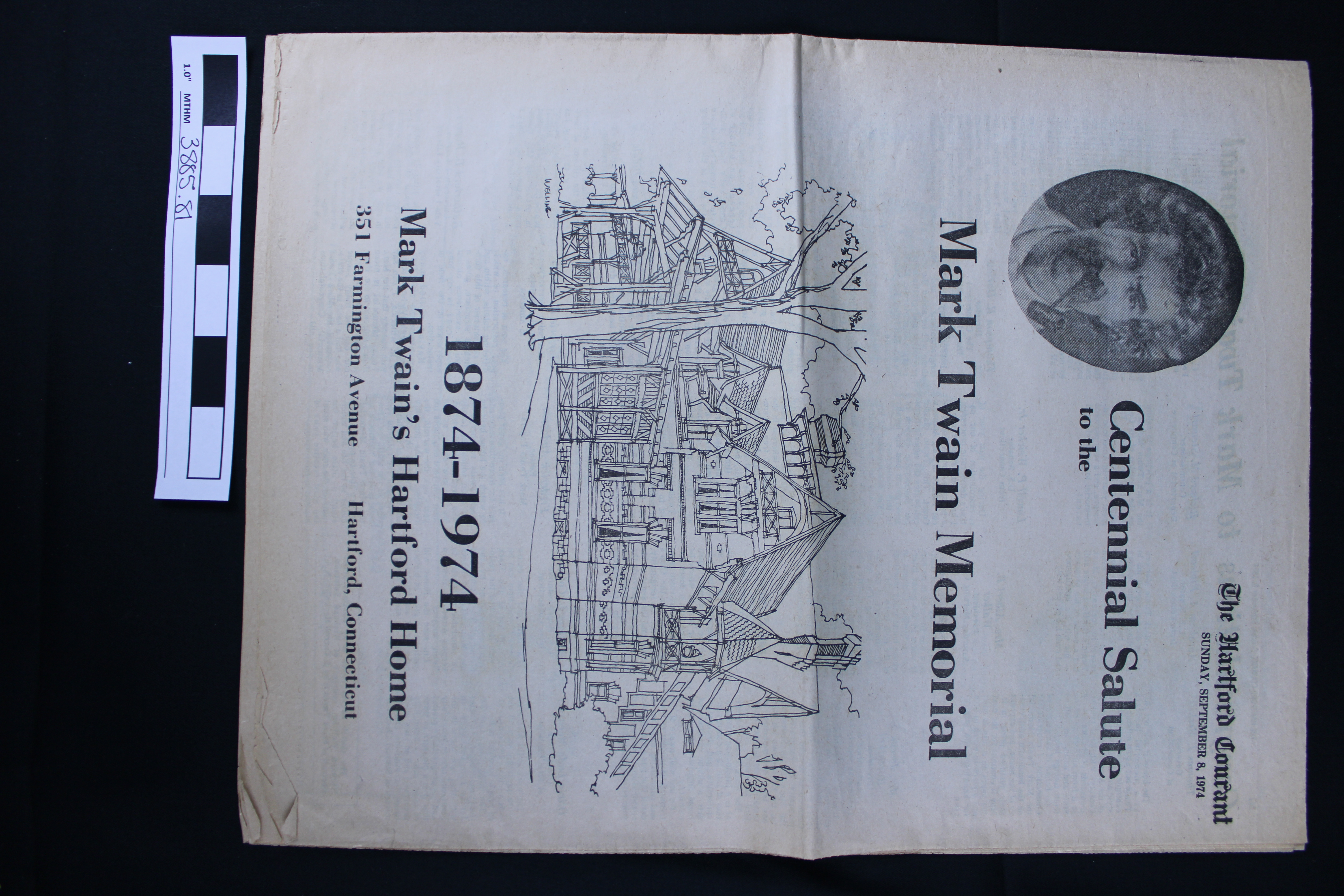

Hartford Courant – formerly 14 Pratt St.

Now the longest continuously running newspaper in the United States, the Hartford Courant was already a well-established pillar of the city when it was based at 14 Pratt Street, where Samuel Clemens, known professionally as Mark Twain, would have found it. It was first founded in 1764 by Thomas Green as The Connecticut Courant. Over the following decades it evolved, experimenting with new names and formats under different leadership. In 1867, former Civil War general and politician Joseph Hawley, leading the Hartford Evening Press purchased the paper that The Connecticut Courant had become, The Hartford Daily Courant. He merged his two papers to make the Hartford Courant that we know today. Author Charles Dudley Warner joined him as co-editor. During their leadership, the Courant became one of the most well-known newspapers not only in the state but the nation.

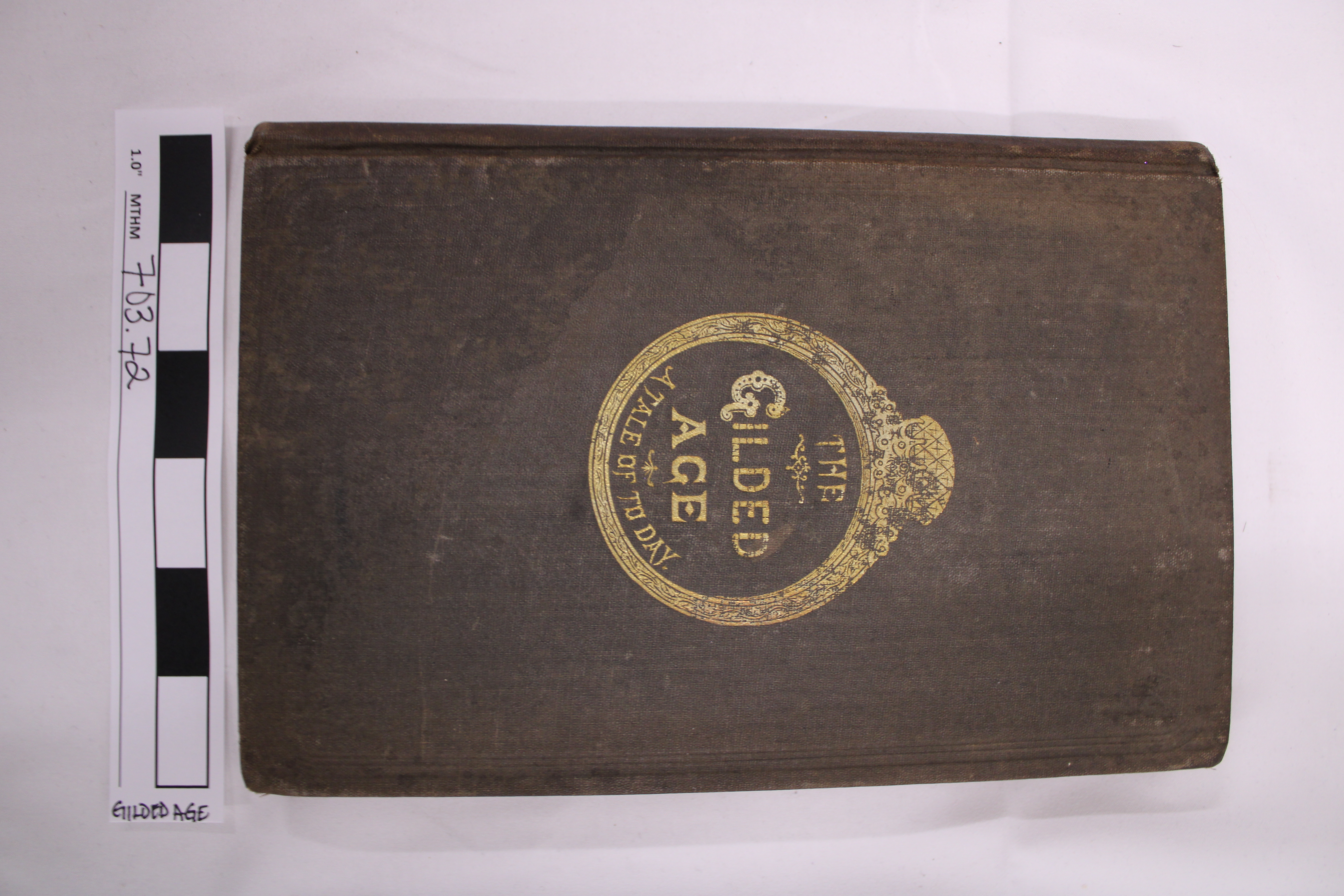

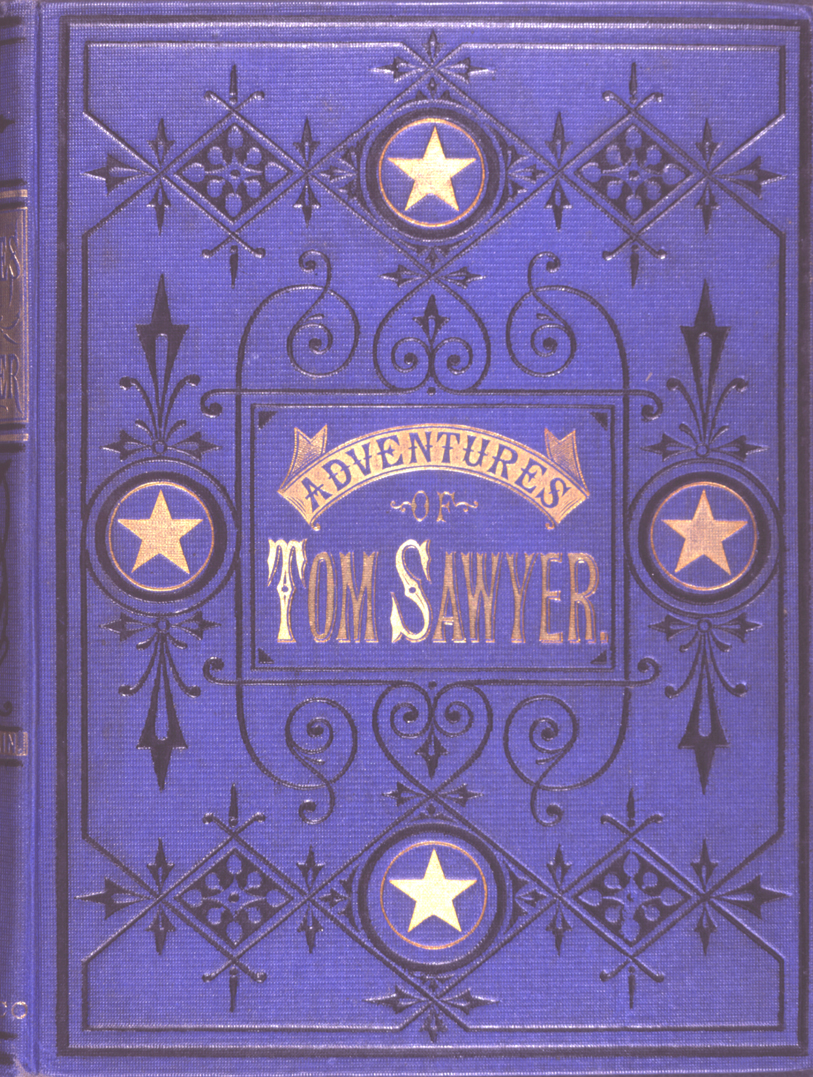

When Samuel Clemens first came to Hartford in 1868, he pursued a partnership in the Courant. He wanted to join with Hawley and Warner, both residents of the influential and affluent Nook Farm neighborhood of Hartford he longed to enter. He was preparing to marry Olivia Langdon, a woman from Elmira, New York far wealthier than he was. In marrying her, he was quite dramatically shifting in class. A partnership in the Courant would have allowed his career to follow that shift while keeping him in the industry he’d worked so long in, from working as a teenage printer’s apprentice in Missouri to a reporter based in California. Ultimately, he was too much of an unknown to Hawley and Warner and the partnership fell through. However, the connections he made lasted. In 1873, Samuel and Charles Dudley Warner published a novel together, The Gilded Age. The title came to exemplify the era they lived in, one characterized by economic disparity, the extreme economic disparity, exploitation, and corruption.

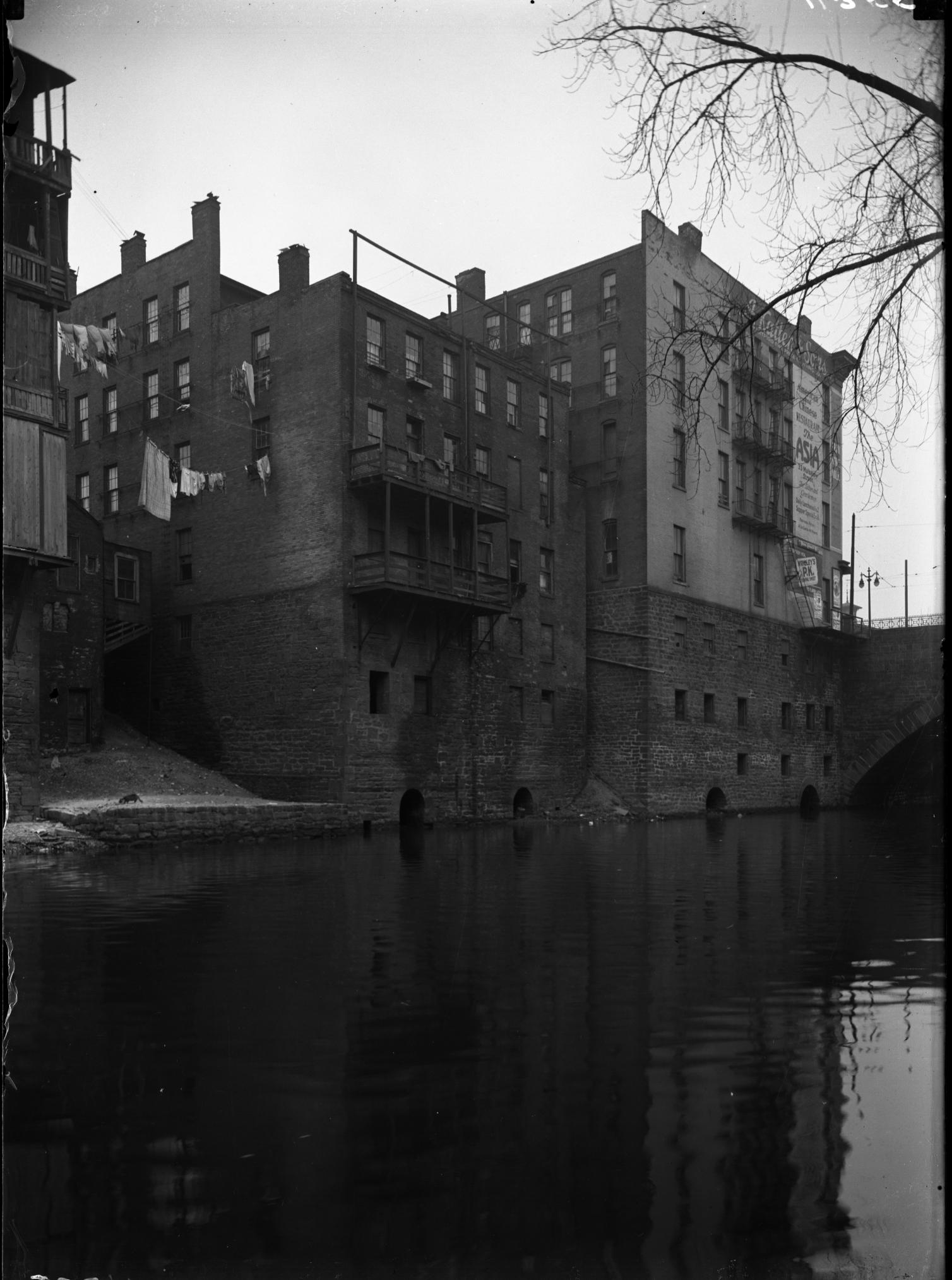

When Samuel and his wife Olivia finally moved to Hartford and Nook Farm in the early 1870s, the Courant integrated them with the new community around them. In 1871, while still renting a house and years before building their own, the family’s check register records them posting an ad for domestic staff. Another entry in 1873 lists them posting an ad looking for a lost pocketbook. Still others show them purchasing subscriptions to the Courant. Through all of these exchanges, they both gained and shared information from and with the broader city, using it to communicate as well as stay connected to current events, market news, and gossip. And each of these monetary transactions, one by one and in tandem with many others, embedded them into a network of financial exchange that included all the trade, industry, and labor that made up Hartford.

Many members of the Hartford workforce would have looked for and found employment in the pages of the Courant. So too many job hopefuls have advertised that they were looking for work. One of these ads from May 8, 1879, from a black man living at 132 Wells Street, who’d been in his current position for four years and was looking for work as a coachman, may even have been posted by George Griffin, who the Clemenses employed as a butler from 1874 to 1891. He likely lived at that address and would fit the description–perhaps he was looking for work options.

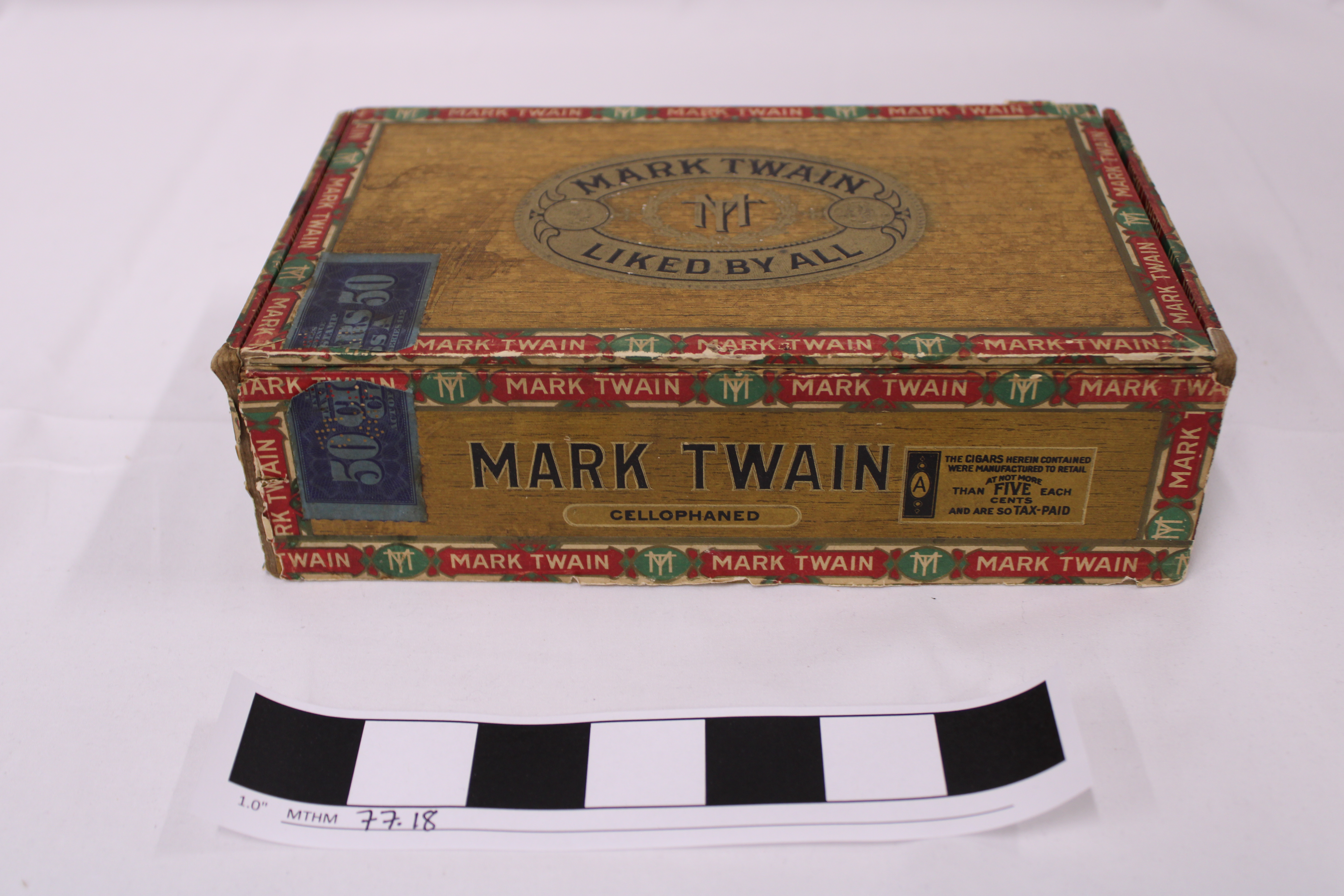

Samuel found himself the subject of a great deal of reporting. Over his years in Hartford, Mark Twain became one of the most recognized American names. The Courant delighted in reporting on the comings and goings and public appearances of one of its most famous locals. This media attention, as well that of countless other newspapers and magazines, helped transform “Mark Twain” from simply the pen name of an author and public speaker into a persona, the eccentric performer and comic rocketed from humble origins to fame and notoriety, separate from Samuel Clemens, the husband, father, and friend. That fame spread to sometimes encompass those around him. The Courant highlighted, in covering the deaths of both Olivia Susan Clemens, his daughter, and Patrick McAleer, his coachman, their connection to the famous Twain and his interest in their passing. These deaths were the tragedies the family and friends Susy and Patrick left behind, but, since that included Mark Twain, they were everybody’s tragedies.

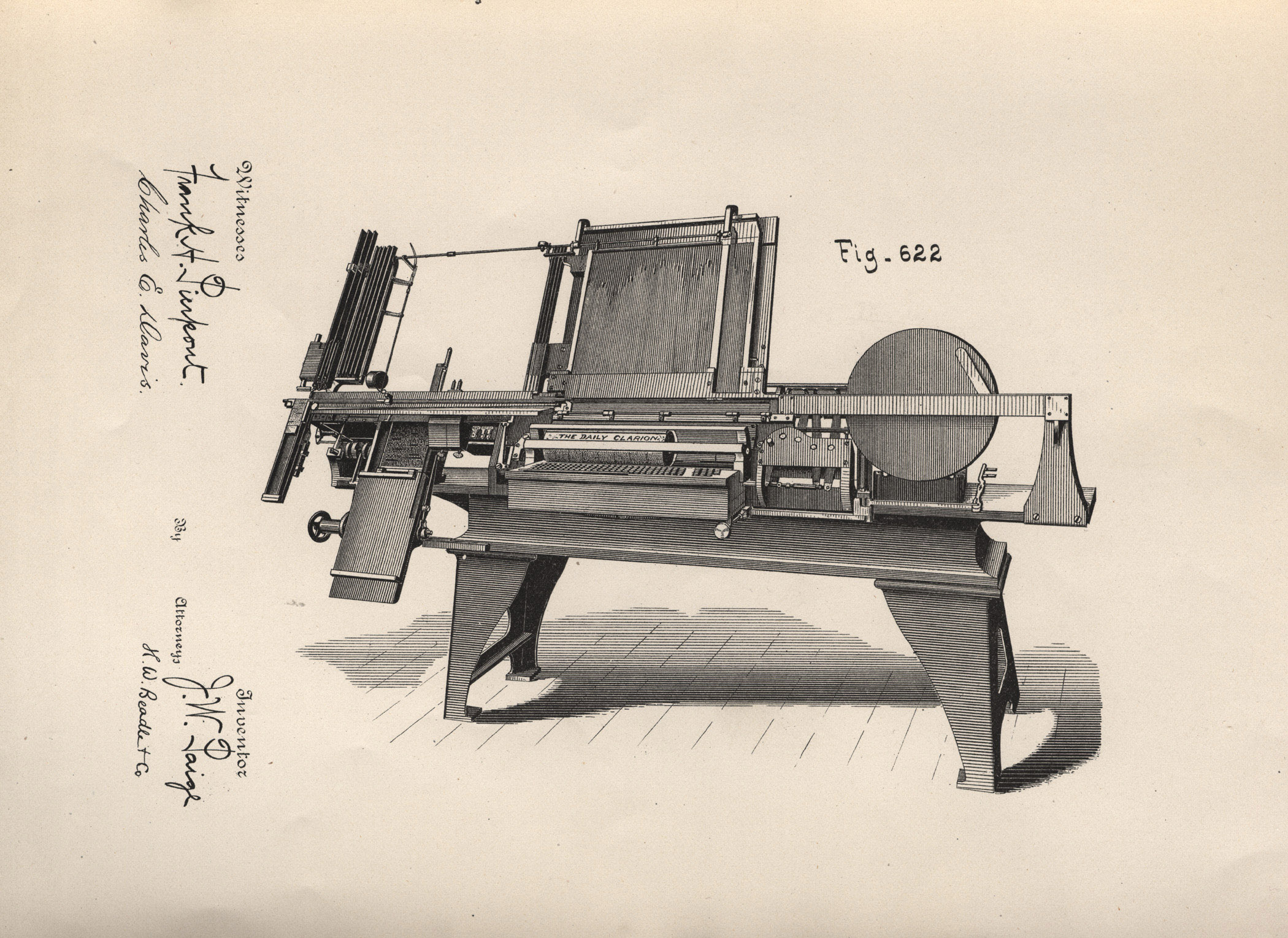

The Courant also became one of Samuel’s experiments. He was a major investor in James Paige’s Compositor, a typesetting machine supposed to revolutionize the printing industry, largely by automating jobs. Samuel proposed to Paige that they use the typesetters at the Courant to identify the speed they worked at which Compositor would need to beat. He suggested a contest among the typesetters for a cash prize but with the purpose concealed, knowing they’d be far less likely to participate if they knew the goal was to eliminate their jobs. Ultimately, with only two compositors fully constructed and many malfunctions, the endeavor was a failure. Paige was only one of several working towards his goal. He found himself outcompeted by more practical machines that ultimately succeeded where his invention had failed to overhaul the labor landscape of printing and, by extension, newspapers like the Courant.