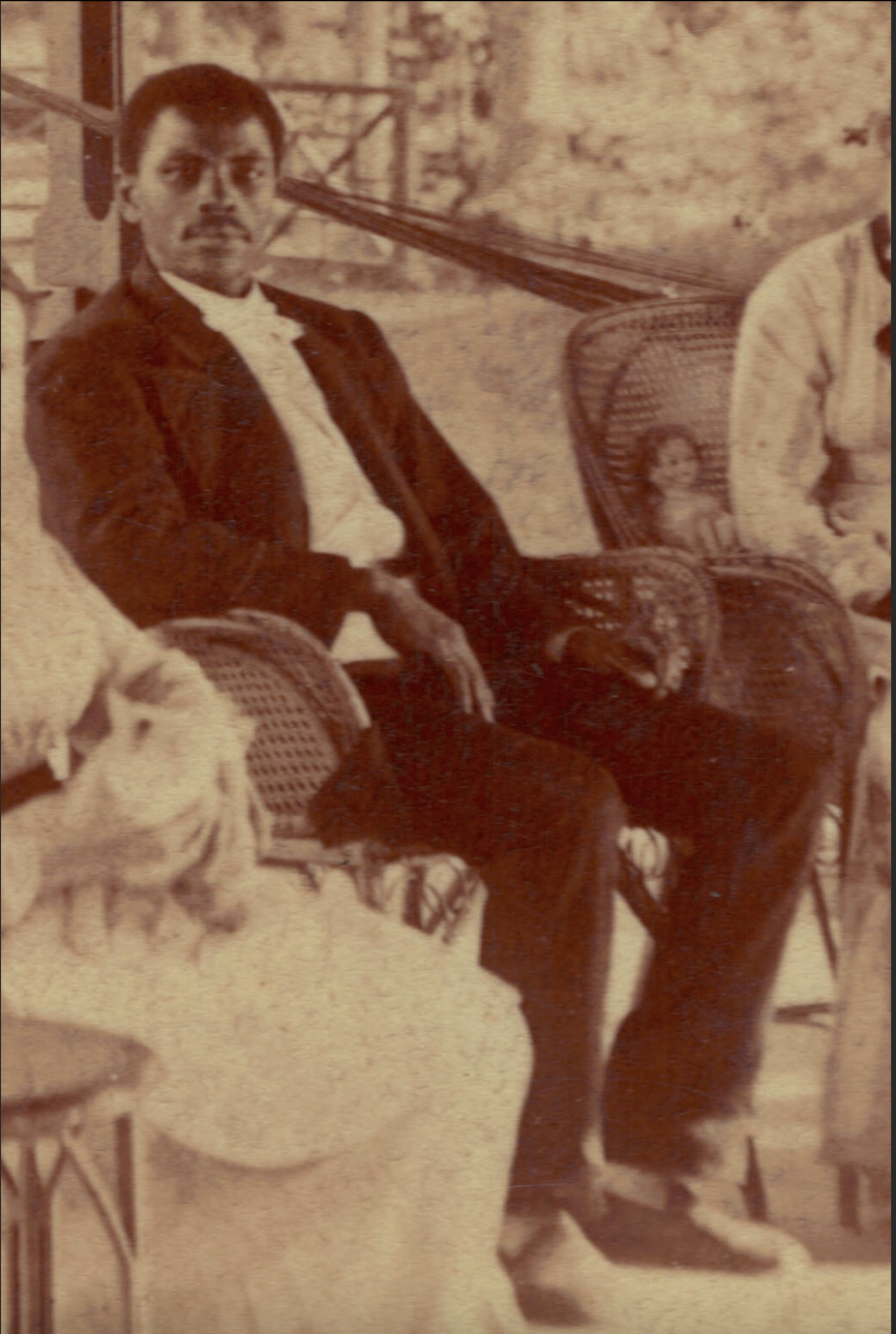

George Griffin (c.1850-1897)

Born enslaved, probably in Maryland, around 1850, George Griffin escaped to the Union Army during the Civil War and served as personal servant to a major general. As an adult he made his way to Hartford where he worked as a waiter at the Allyn House, the preeminent hotel of the era. In his essay “A Family Sketch,” Samuel Clemens recalls that Griffin came one day “to wash some windows and remained half a generation.” While Samuel’s story is funny and can be romanticized, the position of butler was not one that Griffin could have attained accidentally. As head of the household staff (with the possible exception of the ladies’ maid and coachman), this was a responsible, supervisory post. And in 1870s Hartford, supervising white servants was an unusual role for an African American. It is more likely that the two crossed paths in Hartford, possibly at the Allyn House, and Griffin was recommended for the position of butler in the Clemenses’ newly formed household.

As butler, he was a close friend of the family, and a special favorite of the three Clemens daughters; a “deacon & autocrat” of Hartford’s A.M.E. Zion Church; a political force in the African-American community; and an inveterate and brilliant gambler. Clemens calls him “shrewd, wise, polite, always good-natured, cheerful to gaiety, honest, religious, a cautious truth-speaker.”

In the household, Griffin was well connected to the social and political world of the Clemenses. He picked up political gossip, which helped him in his role as a leader of the African American community in Hartford and also gave him important advance information about elections, which Griffin shrewdly used to advance his financial prospects through his side business as a local bookmaker. According to Clemens, five years after Griffin started working for the family, his check was good for $10,000. When financial trouble caused the Clemenses to leave the house in 1891, Griffin secured a position as a waiter at the Union League Club in New York City. At the club, Griffin served “as banker for the other waiters, forty in number,” lending them money “at rather high interest, & as security he took their written orders on the cashier for their maturing wages.” He also lent money outside the club, accepting gold watches and diamonds as security, and “had about a hatful of these trifles in the club safe.” He died, aged about 47, after a full day of work at the club in May 1897.

Griffin was married twice, first to a woman named Rhoda with whom he had a daughter who died in infancy; and then to a woman named Mary with whom he had a son, Lucius, who unfortunately died as a teenager. Mary and Lucious are both buried in Old North Church on the north-side of Hartford. Griffin’s burial is believed to be unmarked in New York City.

In 2024 the Twain scholar Kevin Mac Donnell of Austin, Texas, was able to locate the sole known photograph of Griffin. Mac Donnell also produced the first full-scale biography of Griffin, published in the Mark Twain Journal’s spring issue, which filled out many previously unknown elements of his career and family life.