Education

Susy, Clara, and Jean Clemens girls had their first lessons at home in the schoolroom next door to the nursery on the second floor of their Hartford home. This room was originally their father’s study, but he soon found that he could not work listening to such giggly, tumultuous play next door. Clemens moved out, and the girls moved in with their mother, Olivia, as their first teacher. In 1880 the family hired Lilly Gillette Foote to be their governess for the next eleven years. Ms. Foote and other tutors taught reading, writing, history, arithmetic, literature and science. Clemens wanted them to read German books before English books – his reason being that they would learn English no matter what, and it would be easier for them to learn other languages while they were young. Olivia employed a German nurse named Rosa who always conversed with the children in German so they could practice their skills. The girls also studied piano, singing and social dancing. All these skills were expected of young upper middle-class women.

The two oldest daughters, Susy and Clara went on to attend Hartford Public High School. After preparing to attend Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, Susy Clemens entered Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania in the fall of 1890. The following year Olivia wrote to a friend that Susy was having a difficult time and believed it would be better if she left. A couple of months later Susy returned home and never went back. Clara went in an entirely different direction and spent the last years of the 1890s in Vienna to study singing and consequently started a professional career in Europe and the United States. Like her older sisters, Jean was educated at home during her childhood, however in 1896, she suffered a severe epileptic seizure while attending school in Elmira, New York. Her condition continued to worsen and interrupted her ability to continue her education in a traditional sense. Jean went on to teach herself to type in order to help her father with his manuscripts. She also became a talented wood carver, selling her pieces in order to have some spending money of her own.

Hartford Public High School

The Hartford Public High School traces its history to the Latin School, organized in 1638 by Connecticut’s founder Rev. Thomas Hooker. When Connecticut governor Edward Hopkins died in 1657, he provided funds for a free school in the city. In 1839 there was a proposal to form a high school and in 1847 Hartford Public High School was dedicated. It moved in 1869 to a brick and brownstone school on Asylum Hill and was expanded due to enrollment demands in 1877. Sadly, just a few years later the school was destroyed in a fire and architect George Keller designed a new structure which was enlarged again in 1897.

Although the Clemens daughters received an education at home for their formative years from their mother, Olivia, or their governess Lilly Gillette Foote), Susy and Clara each spent their freshman year at Hartford Public High School, Susy during 1887-1888 and Clara during 1888-1889. They studied math, science, Latin, and history. Susy also studied a little Greek, while Clara dabbled in Modern Languages. The girls did have problems with their behavior. Susy often had unexcused absences and received 11 demerits over the school year. Clara received 13 demerits in one month. (You could receive a demerit for talking back, laughing out loud, or being caught in the hallway during class.)

The school was demolished in the 1960s and replaced with Interstate 84. The present-day high school is located on Forest Street next to The Mark Twain House & Museum, and is the second oldest public secondary school in the country.

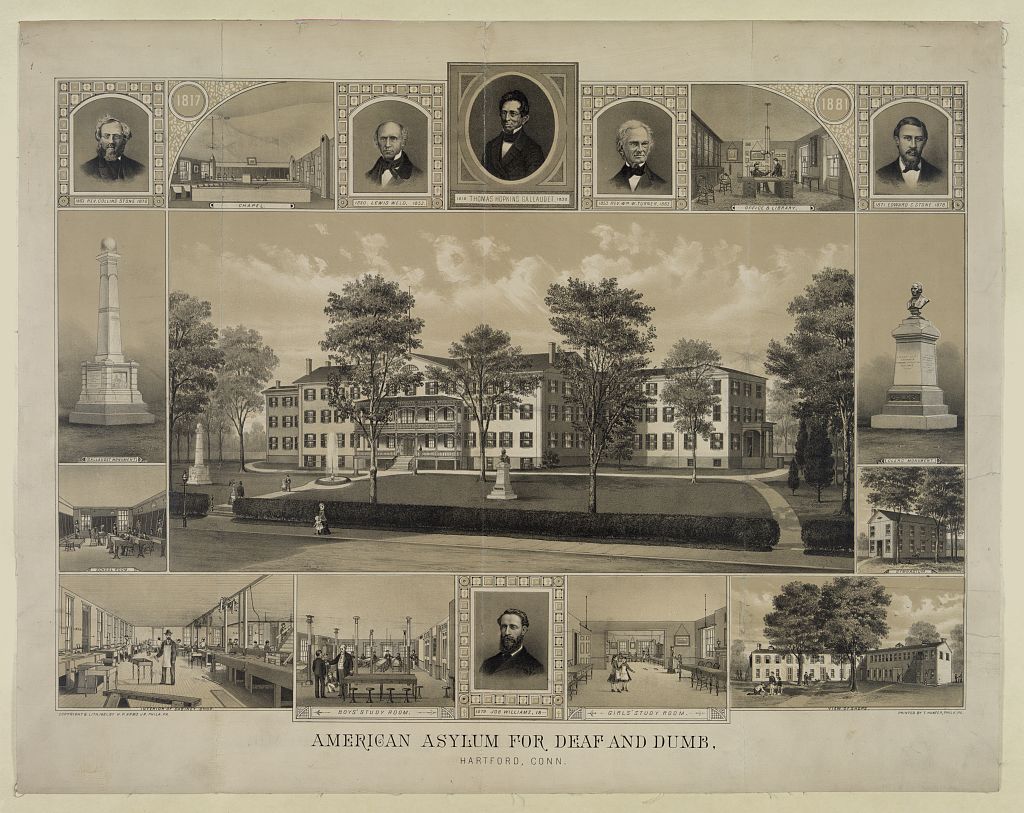

The American School for the Deaf (originally named The American Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb)

In 1814 the Rev. Thomas Gallaudet moved next door to the Cogswell family in Hartford. He noticed that their nine-year-old daughter, Alice Cogswell, who had a serious hearing impairment, had difficulties interacting with other children. He experimented with teaching her rudimentary ways to communicate through pictures and writing letters in the dirt. A group of neighbors became interested in exploring communication and learning among deaf children, inspired by Alice. Gallaudet was chosen to travel to France to study methods of teaching deaf students. He met and hired a talented deaf teacher, Laurent Clerc, to help him found the first permanent school for the deaf in the United States. The two pioneered the use of sign language as a way for the hearing-impaired to communicate. The “Asylum” grew to include a gymnasium and cabinet shop, as the school also trained students for work in industry.

By the time the Clemenses moved to Hartford the “Asylum” was a major civic institution, having given its name to the former Lord’s Hill and to a major avenue leading west from the city. Many of the school’s teachers and administrators were members of Asylum Hill Congregational Church nearby, and Samuel Clemens would occasionally speak there with sign language interpretation. Clemens’s friend Rev. Joseph Twichell was deeply involved in the Asylum’s work, and traveled to Washington, D.C. in 1888 to speak at the college for the deaf there, now known as Gallaudet University.

The Chinese Educational Mission in Hartford, 1871-1881

One evening in the 1870s Samuel Clemens sat down at the piano in the drawing room of his family’s Hartford house, and with the help of Joseph Hawley, Civil War hero, former governor and future Senator, sang African American spirituals, known from his childhood and travels throughout the South, for the benefit of honored guests. These guests were teachers from the Chinese Educational Mission, the first experiment in overseas education by the leaders of China’s Qing dynasty, which brought 120 boys to New England to study in local schools and ultimately, they hoped, U.S. colleges.

The project was the brainchild of Yung Wing, a businessman who had attended a private academy in Massachusetts before becoming the first Chinese graduate of Yale. “I was determined that the rising generation of China should enjoy the same educational advantages that I had; that through western education China might be regenerated, become enlightened and powerful,” he later wrote. The boys, aged 12 to 15, came to America in three contingents, their parents committing to their absence for 15 years. They were put up by families in homes extending from Massachusetts to New Haven. Their base was in Hartford, where the Chinese government built a large headquarters. Here the boys were to convene once a year to keep up with their language and with Confucianism.

Clemens’s friend Rev. Joseph Twichell was a leading booster of the effort, and Yung became a lifelong friend. Sadly, the effort foundered after a decade on the twin rocks of American racism and Chinese conservatism. Anti-Chinese riots on the West Coast led to the Chinese Exclusion Acts, which Clemens called “that infamous Chinese bill.” Meanwhile, conservatives in China became alarmed that the boys were becoming Americanized, some of them even converting to Christianity.

Yung appealed to Twichell to ask ex-President Ulysses S. Grant to use his influence with Chinese leaders to save the mission. Twichell got his friend Clemens, who knew Grant, to help, and the Mission was saved – but only for less than a year. The disappointed students returned. Many later became statesmen, naval officers, railway builders, interpreters and mining engineers. Some were able to return to the United States and finish their studies. Elsie Yung, Yung Wing’s granddaughter, recalled how, when she was a girl in Shanghai, Mission veterans would tell her: “I used to dance with Mark Twain’s daughters.”

Twichell, meanwhile, was prophetic in a speech he gave against anti-Chinese prejudice: “That rising power in the East, with a great future before it, has a memory, and we shall have to pay, in the event, for the liberties we have taken with it.”